Talk of any country’s economic miracle and the conversation inevitably centres around its growth. But, just as important to the miracle story is growth’s irritating cousin, inflation, which latches itself to growth and tries to follow it around. Inflation is a general rise in the price of goods and services and measures a loss of purchasing power. To truly grow, an economy needs to grow at a rate that outpaces inflation - this is known as ‘real growth’. As investors seek shelter from rising inflationary pressures worldwide, China looks to stand apart from the pack, but we look to see if this environment is changing, and what that means for inflation?

In China, the preferred measure of inflation is the CPI, or consumer price index, which measures the average rise in prices as paid by consumers across the economy. The National Bureau of Statistics collects this data through various weightings of ‘baskets’ of goods and services, of which the weightings aren’t disclosed. An example is pork; as a staple of the Chinese diet, it is believed to be the most heavily weighted product, with food, tobacco and alcohol accounting for approximately 30%. Real growth in the country is running high, with CPI and economic growth running at 1.3% and 8.8% respectively in May - can China sustain this trend?

China is a large manufacturing economy, which makes it susceptible to commodities. The moniker ‘Factory of the World’ evokes images of roaring coal-fired smokestacks belching into the sky, but rising tensions with, and a coal embargo on, Australia has caused them to sputter. Coal inventories are declining and prices rising as companies scramble to source new suppliers. A strong rally in oil and steel prices have demonstrated manufacturers’ exposure to these commodities’ volatility. The producer price index (PPI) measures cost inflation for producers, and jumped to 9% in May, led by a 34.3% price rise in the oil and metals sectors, and though PPI’s effect on CPI is muted, it still trickles through. More broadly for consumers, natural disasters have affected food prices as storms rock its top wheat growing areas, and fears of a resurgent African Swine Fever have caused farmers to slaughter their pigs – collapsing pork prices by 65% in the process.

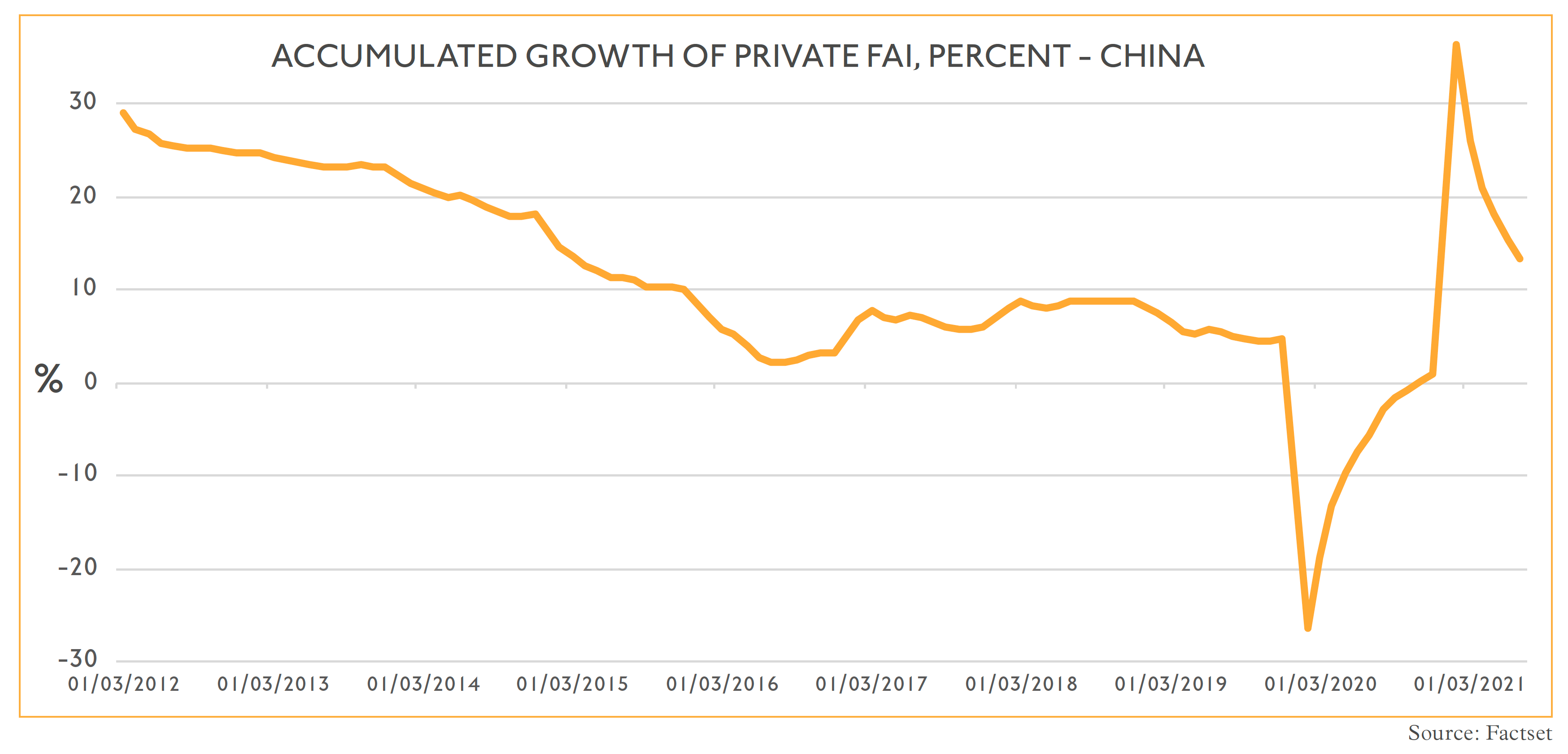

Yet growth doesn’t always cause inflation. By increasing productivity – that’s output, per worker, per hour – a country can produce more goods and services at the same cost, or the same number of goods and services at a lower cost. Good investment is often an effective way of doing this, and investment as a proportion of GDP was 44% in 2020, but still lower than in the past. China’s productivity grew at 15.5% p.a. between 1995 and 2013, but may be experiencing diminishing returns since that figure fell to an average of 5.7% p.a. from 2014 to 2018. Since its economy is still only 30% as productive as advanced economies such as the US and Germany, this appears premature and could mark an acceleration in inflation. It’s important to note that this growth is still impressive; in the same 2014 to 2018 period US productivity growth hovered between 1% and 2%.

This productivity puzzle could be compounded by a shifting regulatory regimen, with a clampdown on the highly innovative technology and education sectors – Chinese technology is worth about US$4tn – potentially stifling future innovation and, by extension, productivity. Though such inflation could be argued as necessary, China’s anti-monopoly agency has approximately 50 staff and is relatively inexperienced. Such a small team has scope for large errors which could increase business costs and translate into higher prices for consumers, while many regulations inadvertently entrench incumbents and reduce competition, further increasing prices.

Inflation indices try to be representative of the economy and, at 25% of GDP, the Chinese real estate market is a significant contributor to inflation. The property market in coastal regions is experiencing soaring prices, where cities have forced developers to sell properties to first time buyers, selecting by lottery. Despite the Hukou system preventing unregistered citizens (of which there are many) from entering these lotteries, odds to win can be as low as 1/60.

China is a tale of two property markets. The government builds housing that lies empty in inland regions, causing excess supply and reducing housing cos; a town in northern China was selling homes for less than the cost of a square metre in Shanghai. This isn’t an issue the Communist Party is happy to let lie, though. New commuter towns are being constructed outside its biggest cities with improved public services and easier Hukou registration. Strict regulation has curbed price growth, and the party has real estate firmly in its sights, understanding affordable housing to be an important lever of maintaining social stability – and its power.

Inflation is influenced by factors domestic and external, and a crisis in global shipping intuitively threatens to disrupt demand for Chinese goods. Yet a voracious appetite for exports has defied intuition, with exports to the EU and US rising 35.9% and 42.6% respectively year-on-year. Meanwhile, the renminbi has remained strong in spite of headwinds - a strong currency reduces the competitiveness of exports while reducing the relative cost of imports, which is ultimately usually reductive to inflation.

In a new focus on self-sufficiency, the party is driving new investments in advanced technologies such as chips. Growing national champions to compete with incumbents will be costly, involving vast sums of investment and decades of patience. If, in the pursuit of economic self-sufficiency, the government compels firms to buy Chinese, they will likely be buying chips of an inferior quality for a higher price – increasing costs, and inflation, while potentially harming productivity.

As investors we must be wary of the underlying assumptions we make. The CPI index in China is often accused of underrepresenting price pressures, due to an underweighting of housing costs. Moreover, in an opaque political system that measures performance by economic metrics, officials have an incentive to place a thumb on the scales.

China’s inflation story has been one suppressed by rapidly growing productivity, developing into an economy surprisingly resilient to volatile commodities. Yet its future appears less simple as the government runs out of low hanging productivity gains to pick. Although a sign the country isn’t immune to runaway prices, China’s real estate market is an early indicator of its willingness to act in the pursuit of sustainable price growth. In a world where the regime claims adroit economic policy as a font of legitimacy, expect inflation to be kept under its watchful eye.

This article was taken from the

August 2021 issue of Market Insight. To subscribe to our investment publications, please visit

www.redmayne.co.uk/publications.